New book gives English Baptists their place in history

Miracles. Tragedy. Heroism. Betrayal. Revelation. Corruption. Adrian Gray explains the background behind his new book and how it is bringing increased interest in Baptist history

About eight years ago a few of us from different churches in North Notts and West Lincs began to put together a project to celebrate the Christian history of our area. This was intended to support our involvement in Mayflower 400 (which has been largely sunk by the COVID crisis) but I also saw two spiritual purposes – history is a great way of getting to speak to secular audiences whilst Christians can only be enriched by better understanding of their own heritage. This idea is developed more widely through Christian Heritage Network UK.

About eight years ago a few of us from different churches in North Notts and West Lincs began to put together a project to celebrate the Christian history of our area. This was intended to support our involvement in Mayflower 400 (which has been largely sunk by the COVID crisis) but I also saw two spiritual purposes – history is a great way of getting to speak to secular audiences whilst Christians can only be enriched by better understanding of their own heritage. This idea is developed more widely through Christian Heritage Network UK.

In our area the story really starts in the early 7th Century with baptisms in the River Trent. Although there is some great medieval material, what emerges after 1500 is how this small region (think 30 miles across) produced many of the key figures of English Christian development after the Reformation. Thomas Cranmer, the architect of the Church of England, was born here; there is John Foxe, who created our images of Protestant martyrdom; those who became the ‘Mayflower’ Pilgrims; the mercurial George Fox from Mansfield who formed the Quakers. Later on, we get to the Wesleys and ‘General’ Booth.

But we must be honest - the story also has its fair share of ‘villains’ including corrupt and venal bishops, despotic leaders who sent those who disagreed with them to the stake or the gallows, on both sides of the Atlantic, and one of Elizabethan England’s most sinister torturers.

To underpin this, I began to research Christianity in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire.

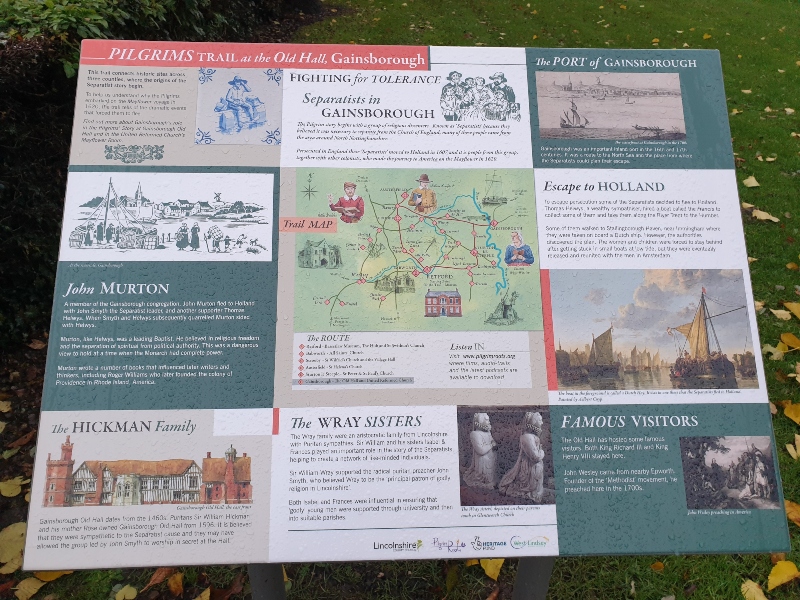

Early on in this work it became clear that almost no-one knew anything about the Baptists, and in most tellings of the story they were omitted. This was especially true of their part in the story of the Mayflower: John Smyth, the founder of the English Baptists, and John Robinson, the ‘Pastor of the Pilgrims’, both came from one village – but guess which one was not even mentioned on the historical information board that used to be there?

Taking the long view in a book has meant that the importance of John Smyth’s Baptist congregation that emerged via Gainsborough and Amsterdam can be shown in true perspective. Smyth was certainly a leading influence on the move of local puritan leaders into fully-fledged separatism around 1606 and behind the move to Amsterdam in 1608. In fact, what little we know about the actual escape of large numbers to the Netherlands revolves around the efforts of Thomas Helwys, his Nottinghamshire friend. You might say that without Smyth and Helwys there might never have been a Mayflower voyage, despite the differences that emerged in the Netherlands when Smyth embraced believers’ baptism and the Arminian belief that all might be saved if they had faith.

One of the arguments about Mayflower 400 has been around whether the ‘Pilgrim fathers’ really do represent the ‘birth of the American Nation.’ Spiritually they plainly do not – by adding together Congregationalists, Lutherans, and Reformed you still have less than half of the population that are Baptist. Smyth and Helwys are therefore as relevant, if not more, to many Americans’ faith heritage than Brewster and Bradford. To this we can add the simple fact that many Pentecostal and ‘new’ churches have also embraced believers’ baptism.

Yet taking the ‘long view’ has also helped a revised focus on what parts of this story matter most. The rediscovery of baptism as a central belief is perhaps matched by another global contribution that Smyth and Helwys delivered into English-speaking communities – for they were the first people in our language to advocate full separation between State and Church including freedom of faith for other religions. Smyth, Helwys and John Murton – all from the Gainsborough congregation – pioneered thinking on religious liberty that crossed the Atlantic with Roger Williams and came back again with Sir Henry Vane. Then came John Spittlehouse, also a Baptist from Gainsborough – the first to argue that freedom from censorship should extend even to the Qu’ran. This story became a major theme of my book, linking our local Baptists to the American First Amendment and the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

Under Cromwell, the Baptists saw the door of freedom swing open and many congregations were planted. Then, in 1660, it slammed shut again. What happened next will form the material for a later book.

Baptist Times, 01/05/2020