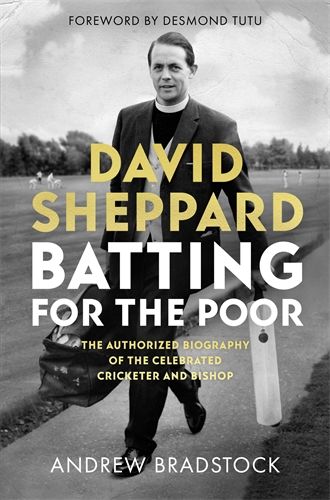

David Sheppard: Batting for the Poor

Batting for the Poor, the authorised biography of the former Bishop of Liverpool and Test cricketer, David Sheppard, has just been published. Here the author, Andrew Bradstock, reflects on his subject and why he wrote the book

David Sheppard may be unique in post-war Britain in becoming a household name in two distinct spheres of service – cricket and the church.

David Sheppard may be unique in post-war Britain in becoming a household name in two distinct spheres of service – cricket and the church.

His career as a cricketer was like a Boy’s Own story. A no-hoper at sport until he was 17, he went on to break records at his school, Sherborne, and make his first-class debut for Sussex at 18.

At Cambridge he set further records as a batsman – most of which are still unbeaten – and was selected for England while still an undergraduate. He played for his country 22 times, including twice as captain. In 1953 he led Sussex to second place in the County Championship, at that time their joint highest position.

In addition to his achievements on the field, Sheppard played a leading role in bringing down apartheid. He was the first Test player to refuse to play against a team calling itself South Africa but selected entirely from the country’s white minority, and became a leading advocate of a sporting boycott of the country. This proved effective in bringing change, but made him very unpopular with friends and colleagues in cricket, and with sections of the media.

Sheppard played first class cricket until he was in his 30s, but after Cambridge he stepped back from the game to train for ordination. After a curacy in Islington, he spent ten years as warden of the Mayflower Family Centre in Canning Town, before being appointed Bishop of Woolwich and then Bishop of Liverpool. Again, he was constantly in the public eye, firstly as a spill-over from his fame as a sportsman, but increasingly because of his passion for the inner city.

His time in Islington and east London challenged him deeply about conditions in our cities, and as a bishop he worked tirelessly to expose the evils of poverty, unemployment, poor housing and racism. He was the main driver of the Church of England report, Faith in the City, published in 1985, which played a major role in changing attitudes to the inner-city within both Church and government.

In Liverpool he is best remembered for his friendship with his Roman Catholic opposite number, Archbishop Derek Worlock. During their 20 years together they worked tirelessly to end the deep religious divide in their adopted city.

They were not the first church leaders to develop a friendship, even in Liverpool, but against the backdrop of the city’s sectarian past their collaboration was remarkable. Their decision to do everything together, and be seen to be doing everything together, played a significant role in changing the culture of a city often referred to as ‘the Belfast of England’.

It is a measure of their achievement that they could say, after 20 years together, the people in Liverpool ‘have come to expect the Churches to act together.’

Researching Sheppard’s life has been a hugely absorbing task. His daughter, Jenny, and literary executor, Canon Godfrey Butland, kindly granted me access to his private papers, enabling me to discover much new information about his life and the events in which he was involved. The more than 250 interviews I conducted with people who knew or worked with Sheppard also gave me a wealth of new information.

His relationship with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and the question of whether she might have appointed him Archbishop of Canterbury, get full treatment, as does his high-profile spat with one of her ministers, Norman Tebbit, over Faith in the City. I also shed new light on the impact that report had on government policies on the inner city.

I have been critical of Sheppard when I felt it was warranted. He was often faulted for prioritising national – and even international – issues over his diocese, and of being patrician in his approach to tackling poverty.

His obsessive work pattern took its toll on those close to him, particularly his wife Grace, and I explore this more hidden side of his character. The access I was given to Grace’s diaries enabled me to shed fresh light on their relationship.

Grace figures prominently in the book, with her remarkable journey from being a support to her husband, to developing a career and ministry in her own right, discussed in full.

Spending four years with David Sheppard has, not surprisingly, given me food for thought. At the heart of his story was his dramatic conversion to Christ as a student, and I was often challenged as I studied his faith and firm commitment to do what he felt to be right without fear of the cost. His was a model of leadership from which we can learn much today.

I also look at the way his understanding of the gospel both broadened and deepened. At first he viewed it solely in terms of personal conversion, but later recognised it had something to say about wider economic and political issues. He never lost his belief in the gospel’s power to transform individual men and women, but accepted that it also spoke to the conditions in which people lived and their responsibilities one to another. He would often describe himself as a ‘not only… but also’ Christian.

Another impressive aspect of Sheppard’s ministry was the way he used his access to high places for the benefit of those who had no voice. He was also deeply committed to reconciliation. He would never personalise disagreements, and worked assiduously to bring opposing communities together to work through their differences and find a mutually beneficial way forward.

Sheppard’s memorial in Liverpool Cathedral carries some beautiful words from the prophet Jeremiah: ‘Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you… and pray to the Lord on its behalf’.

These perfectly encapsulate Sheppard’s ministry, which I hope I have been able to reflect in the book.

Andrew Bradstock has been researching, teaching and writing about the relationship between faith, politics and social engagement for more than 30 years. After gaining degrees in Theology, Politics and Church History from the universities of Bristol, Kent and Otago, he lectured for eight years at colleges of higher education in Southampton and Winchester and held positions with the United Reformed Church (Secretary for Church and Society) and the Von Hügel Institute at Cambridge (Co-Director of the Centre for Faith and Society).

Do you have a view? Share your thoughts via our letters' page.

Baptist Times, 07/02/2020