Protests or race riots?

Justice enabler Wale Hudson Roberts reflects on this summer's race riots, the conditions that contributed to them and the growing normalisation of racism felt by Black and Brown people.

In doing so, he asks: what role can Baptists Together play in addressing the voice of the far right, Islamophobia, and racism in church and society?

The 2024 race riots are not the first, and unfortunately, they will not be the last. In August 1919, race riots erupted in the UK. Like most riots, whether race-related or otherwise, their emergence is neither sudden nor occurring in a vacuum. The highly competitive nature of the job market and the perception that new arrivals were ‘stealing’ jobs from the majority white British workers provided the backdrop for the 1919 riots.

Months of turmoil ensued, resulting in five fatalities as well as the vandalisation of homes and properties.

If lessons had been learnt from the 1919 race riots, perhaps the 1958 Notting Hill Race Riots might not have occurred. The Government’s invitation to Caribbean immigrants to help rebuild the UK’s crumbling infrastructure was met with incredulity, hostility, and violence from many within the indigenous community, particularly the ‘Teddy Boys’ and the White Defence League. London’s Notting Hill became the scene of some of the worst racial violence Britain has ever witnessed. Like the 1919 race riots, competition for jobs was, we are told, the trigger.

Fast forward to 1985, and Brixton became the site of more racial violence. Dorothy ‘Cherry’ Groce, a Jamaican immigrant, was suspected of harbouring her son, Michael, who had a criminal record. The Metropolitan Police raided Cherry’s house in search of her son.

Her shooting by a Met Police officer left her paralysed, aggravating the already simmering tensions within the community: cars were burnt and used as defensive walls, and local shops were looted. In the same year, the Tottenham race riots erupted.

2024 - the far right and a lack of moral leadership

Now in 2024, social media and its ability to circulate inaccurate information have certainly inflamed tensions. But more importantly, the rise of the far right in Europe and the lack of moral leadership from powerful elements of those in parliament have played an even greater part in this disturbing turn of events.

The far right embodies the worst of the European ideological tradition—anti-immigrant xenophobia, anti-establishment populism, anti-inclusion, opposition to globalism, and a commitment to ethnic exclusivity. It offers its many followers an exclusive identity, advocating simple and expeditious solutions—solutions that demand the exclusion and expulsion of Black and Brown foreigners and the overthrow of the ‘political class.’ It is obsessed with the notion of a sacrosanct nation and its own ethnic purity.

In places like Italy, Hungary, Portugal, Spain, France, and Germany, this rhetoric is on the rise. Some people may be surprisingly ambivalent about the causes of this worrying phenomenon, but we are in a nation led for three years by a Prime Minister who used racial slurs against Muslim women and African children, in which newspaper columnists felt emboldened to use terms such as ‘vermin’ when describing asylum seekers.

Such a nation is destined to sleepwalk into racial violence.

The Rwanda Plan and the Windrush scandal

The obvious ramifications of the frequent culture wars were prophesied and forewarned but went unheeded; The Rwanda Plan and the Windrush scandal are symptoms of this.

In April 2022, the government announced that any asylum seeker entering the UK ‘illegally’ after 1 January 2022 from a safe country such as France could be sent to Rwanda. Their asylum claims would be processed there rather than in the UK, and if successful, they could be granted refugee status in the landlocked East Central African country of Rwanda. This proposed policy, widely condemned by leaders across numerous church traditions, demonstrated the absence of moral leadership and a complete disregard and respect for Black and Brown people. Words like ‘expendability’, ‘dispensability’, and ‘surplus to requirements’ are just a few of the messages this policy communicates to Black and Brown communities.

The Windrush Scandal, which saw hundreds of Caribbean immigrant communities living and working in the UK being wrongly targeted by immigration enforcement, has contributed to creating a hostile environment for many Brown and Black people.

'The increasing normalisation of racism'

The evidence is now incontrovertible, considering what feels, for many Brown and Black people, like the increasing normalisation of racism encouraged by the far right.

While the physical violence has subsided, the verbal assaults and relentless microaggressions will likely worsen. I had to discourage some worshippers from the church I serve from visiting Cowley town centre out of fear they may be impacted by the pockets of localised violence now rearing their head in the aftermath of the national Islamophobic race riots.

The stark regional disparities that have incorrectly and unwisely been attributed as the motivation behind the race rioters need to be addressed urgently. But this social challenge has nothing to do with the actions of racist rioters. ‘Putting Britain first by any means necessary’ remains their number one focus.

What can Baptists do?

So, what role can Baptists Together play in addressing the voice of the far right, Islamophobia, and racism in church and society?

An accurate interpretation of the 2024 riots is a starting point. A blunder was made by much of the media when describing the riots as ‘demonstrations’ or ‘protests’. The 2024 race riots were not born of ‘legitimate grievances’ about poverty and the breakdown in basic services.

Despite the discomfort some may feel in using the words ‘race riots’ to describe what we have witnessed on our streets, race riots are what they are, and we do well to call them out for what they are. They are not, as some might think, protest marches that morphed into violence.

On the contrary, the far right executed a campaign of terror on the bodies of Brown and Black British citizens and Brown and Black foreigners. As Baptists, we may be tempted to describe the violent gatherings as protests in the hope of averting conflict and placating concerns—but this would invalidate the reality and impact of racialised terror on Black and Brown bodies. This is a failure to speak truth to power, and neither is it advocacy, which demands truthful listening and truth-telling.

A theology of advocacy has now become even more necessary. Many of the world’s problems happen because of a failure of sight. Advocacy demands more than mere words; it is wisdom in human flesh, woven into the fabric of everyday life; the relentless cry for revolution on behalf of and alongside the othered; a call for the Kingdom of God to come now.

Advocacy should not be about solving problems in the Western sense of the definition, but listening and building relationships, listening to the othered envision new and creative paradigms, and working in support to foster from the othered the kind of revolution that emanates from the Lordship of Christ.

Advocacy is not a movement away from the Gospel, but a response to it—in this context, and on this occasion, a response by privileged White Baptists who are surely obligated, with and on behalf of Black and Brown Baptists, to offer some hope to a frightened and beleaguered Black and Brown Baptist community.

The power of congregational worship, through the hymn We Shall Overcome, provided some hope for African Americans crushed by the race riots during the Civil Rights Movement. When the hymn was sung, usually at the beginning and end of most Civil Rights meetings, or the end of Sunday worship, the hymn took on the power of a benediction. Shoulder to shoulder, with right arm over left, We Shall Overcome became a redemptive hymn.

The words from the hymn may appear repetitive and even simplistic, but its theology facilitated and sustained years of activism, supported igniting social reform, and offered hope to Black American Baptists and others.

Hope for Black and Brown British Baptists can be similarly expressed. Selecting a song or a hymn that resonates with Brown and Black experiences, embodying a theology of hope—sung ahead of a gathering or during congregational worship—will not only give voice in song to those who are unseen and unheard but act as a powerful symbolic reminder to the unseen and unheard that God sees them.

He hears their yearning for a church and society that will one day be free from the sins of Islamophobia, racism, and race riots.

Wale Hudson-Roberts is the Justice Enabler of the Baptist Union of Great Britain, and pastor of John Bunyan Baptist Church in Oxford

Related:

A response to the violence across UK towns and cities, by President Steve Finamore

'We recognise there are those in our communities who have concerns around immigration, we recognise too that many of them are as appalled by the violence as we are. The challenge now is to find ways to ensure those disseminating inflammatory lies, racism and hatred are confronted and face justice, while spaces of listening and constructive dialogue can be found for those desperate to have their concerns heard.'

The Church, the far right, and the claim to Christianity

The far right has grown in prominence in recent years - with some cynically employing Christian-sounding language even though their allegiance and values are quite contrary to Christian ones. Helen Paynter highlights the current context - and how the Church can respond

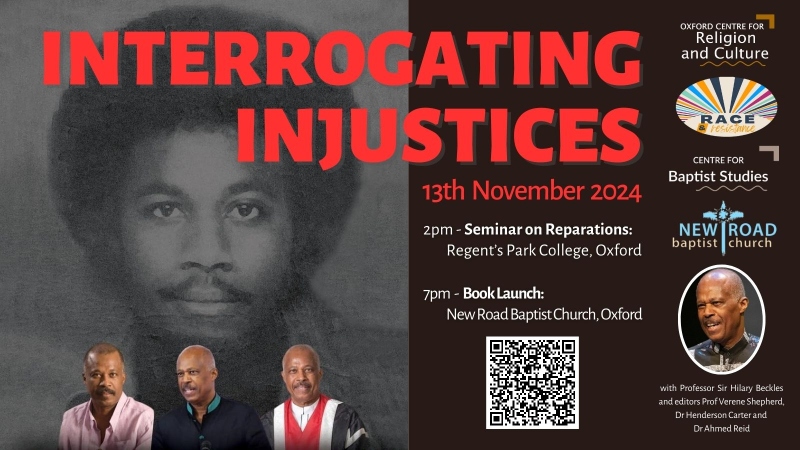

Interrogating Injustices - 13 November 2024

The Centre for Baptist Studies, in partnership with The Oxford Centre for Religion and Culture, The Race and Resistance programme and New Road Baptist Church, are hosting two events on 13 November.

2pm - Seminar on Reparations (in The Collier Room, Regent’s Park College)

7pm - Book Launch for ‘Interrogating Injustices’ published in Sir Hilary Beckles’ honour and edited by Prof Verene Shepherd, Dr Henderson Carter and Dr Ahmed Reid. The evening event will also be live-streamed if you are unable to attend in-person.

is one of the standout, world leading historians on the history of the Caribbean, particularly the transatlantic African Maafa or the trade in enslaved Africans and has helped to lead the call for Reparations for the legacy of slavery.

More details and links to register here

Image | Manchester, August 2024 | Dylan4photography | Unsplash

Do you have a view? Share your thoughts via our letters' page.

Baptist Times, 02/10/2024