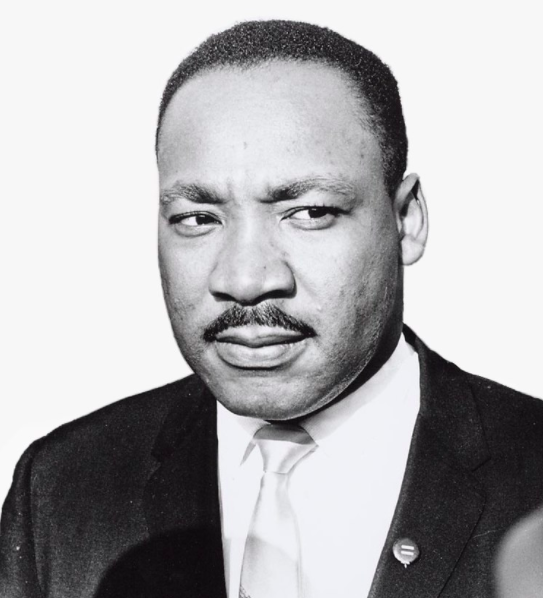

Martin Luther King: his legacy to the church

Putting concrete problems at the heart of theological discourse alongside a commitment to ecumenism in the public square, Martin Luther King set a new standard for church-based social activism. By Wale Hudson Roberts

The fact that King, the highly respected Civil Rights leader, was also a pastor of a Baptist church, can so easily slip our minds. Church mattered to King.

He often reminded his church of its responsibilities to the international community. 'The church,' he said, 'should teach a world view, make it clear that racial segregation is morally evil, expose the thought of segregation in thought and life, open channels of communication between races, develop better programs for racial justice and other social causes.’

He also believed that the church should become a major asset, indeed an indispensable vehicle, in the global war on poverty and economic injustice. For King, the story of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:29-37 provides a model for how the church should relate to wider society. King argues that the Samaritan should be a reminder of how Christians might remove the cataracts of provincialism from our spiritual eyes and see all people as people created in the image of God.

As a Baptist minister, catapulted to the forefront of the Civil Rights movement, ecumenism mattered to King. Consistent with his Baptist roots, King brought ecumenism into ‘the public square.’ The civil rights movement became a visible expression of active unity bringing together voices from a range of denominations each committed to advocacy. Cooperative church and interfaith activism became his rallying cry, taking precedence over creeds, labels and traditions that divided those involved. ‘The greatest ecumenical council the world has ever known,’ is how King described his movement for transformative justice.

Fifty years after his death, an anniversary marked by the globe on 4 April, I’m struck at how often British Baptists forget that theologies also mattered to King. His was a theology committed to the struggle to transform the world for good, as well as a willingness to sacrifice his or her life in the quest for justice for the oppressed. The concrete problems of the community must be grist for the theological mill. Matters concerning black, and gender, oppression, poverty and class dislocation should not be located on the peripheral of theological discourse, but at the very heart of theological attention – where it matters – King would argue.

‘In a real sense, all life is inter related. All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.’

These words, penned by King while in jail in Birmingham, succinctly embodied his theological emphasis and brilliance.

Among the many issues that mattered to King, the coming kingdom, which he saw as a new social order, or a global ‘beloved community’, mattered most. Small wonder that in his last years he turned to issues of poverty and peace, setting a new standard for church-based social activism.

Fifty years after his death his legacy continues. His commitment to church, global advocacy, ecumenism in the public square, underpinned by a black liberation theology, are concerns that should not only matter to Baptists, but all of God’s creation.

Image | By IISG Photograph: Ben van Meerendonk Derivative work: Jahobr - This file has been extracted from another file: 08-15-1964 20069 Martin Luther King (4086739403).jpg, CC BY-SA 2.0 | Wikimedia Commons

The Revd Wale Hudson-Roberts is the Justice Enabler of the Baptist Union of Great Britain

Baptist Times, 29/03/2018